The Rookery

The Rookery Building in the heart of Chicago’s financial district stands testimony to the resilience and creative spirit of late-nineteenth century Chicago. The rebirth of the city in the wake of the Great Fire of 1871 gave rise to the multi-storied office building that would transform the landscape of America’s cities. Amidst the atmosphere of experimentation and innovation that defined post-fire Chicago, the architectural firm of Burnham and Root rose to prominence. Daniel H. Burnham (1846-1912) and John Wellborn Root (1850-1891) formed their partnership in 1873. By the time they received the commission for The Rookery, in 1885, the firm had already established a strong reputation in tall commercial structures.

Completed in 1888, Burnham and Root’s eleven-story Rookery was one of the tallest buildings in the world at the time. Following the Chicago Fire, a temporary city hall and water tower were erected at the corner LaSalle and Adams streets. These buildings were known popularly as “the rookery” because of the many birds that roosted there and the likelihood of being “rooked” by the politicians in residence. Evoking the historical origins of the building’s name, Root playfully incorporated a pair of carved rooks into the Romanesque archway of the main entrance on LaSalle Street.

The Rookery is a transitional structure in the history of American architecture, incorporating both masonry and metal construction methods. Masonry piers support the outer walls, while the inner frame is built of steel and iron. To erect such a massive structure on Chicago’s soft clay soil, Root devised an innovative “floating foundation,” a network of iron rails and structural beams encased in concrete, that supports the building's immense weight. In addition to this innovative method of construction, the building incorporates many other features that heralded the arrival of the modern age including passenger elevators, fireproof construction, and electric lighting.

With electricity in its infancy, Root designed the building to deliver as much natural light to the interior as possible. A hollow square in plan, The Rookery’s offices open to either the exterior, or face inward to a central light well at the core of the building and open to the sky above. At the heart of The Rookery is the light court, a two-story space of wrought iron and glass. Illuminated by natural light from the well above and sheltered from the elements, the light court inspired one contemporary critic to proclaim, “There is nothing bolder, more original, or more inspiring in modern civic architecture than [the Rookery’s] glass-covered court.”

In 1905, seeking to modernize the interior public spaces of The Rookery, Edward C. Waller, the building’s manager, hired Frank Lloyd Wright. While Wright had retained office space at The Rookery from 1898 to 1899, his connection to the building and its architects ran deeper. Waller was a friend and patron to Wright, commissioning numerous residential and public buildings during the architect’s early career. In 1893, following Wright’s departure from Sullivan’s office, Waller engineered a meeting between Wright and Burnham. Burnham recognized the young architect’s potential. He came to the meeting with a unique offer that Wright would later recount in his autobiography, “[Burnham] would take care of my wife and children if I would go to Paris—four years of the Beaux Arts. Then Rome—two years. Expenses all paid. A job with him when I came back.” Despite the generosity of Burnham’s proposal, Wright felt that immersion in European classicism would arrest his own development of an American style of architecture. To Waller’s dismay, Wright turned Burnham down.

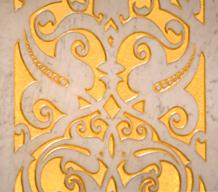

The Rookery commission resulted in one of the most luxurious interiors of Wright’s career. The renovation retained the grandeur of Root’s plan but simplified its decorative scheme. Wright removed much of Root’s ironwork, replacing it with white Carrara marble, incised and gilded with ornament derived from Persian design. The arabesque patterns in the marble honor the nineteenth century design sources of Root’s exterior ornament for the building. Wright’s highly successful renovation transformed The Rookery into a gleaming white and gold center of commerce, possibly an oblique reference to the achievement of Burnham’s 1893 White City, which still lingered in the popular imagination.

In The Rookery light court, Wright demonstrated an ability to skillfully integrate his own design into an existing design by Root, without diminishing the original. Burnham and Root were leading Chicago architects when Wright was beginning to claim his own place of distinction. His respect for their achievement is clear in his grand and exquisite renovation of The Rookery light court.

In 1931, The Rookery underwent an additional renovation by William Drummond, a former employee in Wright’s Oak Park Studio, and in 1992, the building was meticulously restored to its 1905 appearance. The Rookery is a cornerstone of Chicago’s rich architectural history, bringing together the work of two of the city's great design architects, John Wellborn Root and Frank Lloyd Wright.