The Oak Park Studio

In 1893, Frank Lloyd Wright resigned his position as draftsman for Adler & Sullivan and entered private practice, establishing an office in the Schiller Building in downtown Chicago. At the time Wright founded his practice, the American architectural profession was coming into maturity. The independent builders and contractors that traditionally had served as architects in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries were replaced in the post-Civil War period by professional architecture firms that arose as the United States established itself as an urban nation.

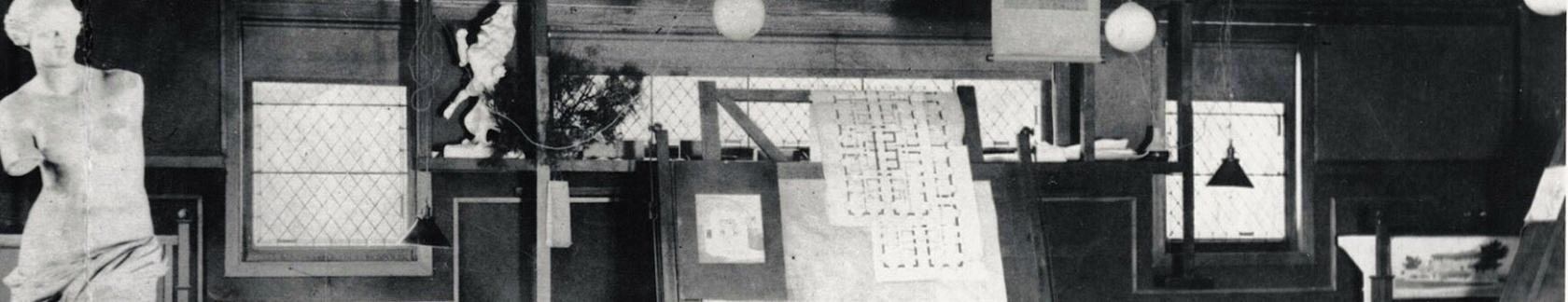

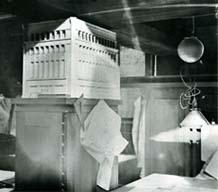

In 1898, with funds secured through a contract with the Luxfer Prism Company, Wright built a new studio addition to his Oak Park residence. It was here that Wright pioneered a unique new vision for American architecture, the Prairie style. The Oak Park Studio years were an incredibly prolific period in Wright’s career, with more than a third of his life’s work produced at the site between 1898 and 1909. Major buildings of the Prairie style, including the Larkin Building (1904-06), Unity Temple (1905-08), and Wright’s Prairie style masterpiece, the Frederick C. Robie House (1908-10), were all designed at the Studio.

Contributing to the legacy of Wright’s Prairie years were a group of talented young draftsmen, architects and artists drawn to the Studio by Wright’s vision. These included Marion Mahony, the first practicing woman architect in America, Walter Burley Griffin, William Drummond, Charles E. White, Francis Byrne, George Grant Elmslie, Frances Sullivan, John S. Van Bergen, Andrew Willatzen, George Willis, Harry Robinson, Richard Bock, George Mann Niedecken, Orlando Giannini and Isabel Roberts.

The individuals who worked for Wright came to the Studio with varying degrees of experience. During the early years of business, the principal staff members, Mahony, Drummond, and Griffin, were academically trained and professionally licensed architects. These skilled practitioners were instrumental to Wright as he worked to master his vision for a new American architecture. Francis “Barry” Byrne, who entered the Studio as an inexperienced novice in 1902, recalled an “almost constant dialogue,” between Wright and Griffin, “which… profited both in clarifying architectural issues as the work in the office presented.” The sculptor Richard Bock, who worked on numerous commissions for Wright, including the sculptural additions to the Studio façade, remembered Marion Mahony as, “a brilliant intellectual and a match for Wright in debate. She served as a source of practice and training for his lecturing.” In later years, with his vocabulary of design for the Prairie House fully realized, Wright would rely on less experienced staff, with less imposing personalities.

Despite their varied backgrounds, Wright’s staff was united ideologically. They were strongly influenced by the principles of the Arts and Crafts movement. They shared a reverence for the natural world, derived in part from the transcendentalist writings of Whitman, Thoreau, and Emerson. They were inspired by the teachings of Wright’s mentor, Louis Sullivan, but above all they shared Wright’s desire to create a new, democratic architecture, free from the shackles of Old Europe, and suited to a modern American way of living.

Surviving documentation from the Studio years depicts an inspiring environment, brought to life by the vibrant personalities of those who worked there. Against the backdrop of one of Wright’s most significant early buildings, the Studio staff engaged in lively critiques of each other’s work, interacted with artists and craftsmen, and debated art, architecture, and politics. Charles E. White, who worked as a draftsman at the Studio between 1903 and 1906, wrote of his experiences, “my environment is changing my character from day-to-day, architecturally as well as in other ways.”

Working in Wright’s Studio was a life-changing experience for many of his staff. Careers were defined, friendships made and lost, and future spouses met and courted. The years spent with Wright would have a lasting impact upon his staff. After leaving his employ, many of the individuals who worked at the Studio would play a critical role in the development and dissemination of the Prairie style of architecture.